-

How is an epidural for childbirth done?

Your doctor, the anesthesiologist, or nurse anesthetist will place the epidural after your obstetrician decides you're ready and it is safe to proceed.

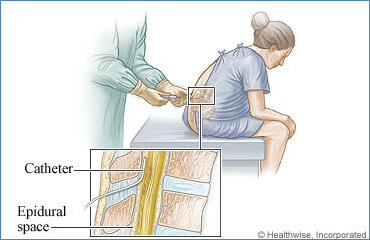

How well you get into position really helps determine how easy or difficult it may be to place your epidural. We will either have you sitting with your back curved out or lying on your side with your knees pulled toward your belly. Your anesthesia provider will ask you to be as still as possible. We know this can be difficult especially when in active labor, but it really helps speed up the epidural placement and limit your complication risk. Local anesthetic will numb your back first. Then we will utilize a needle to access the epidural space in your back through your anesthetized skin. You should only feel some movement or pressure, but not needle pain at this point. A tiny epidural catheter will be advanced through the needle into the epidural space. We take out the needle and start using your epidural tubing. If you are in labor the medicine we inject may take about 15 minutes to really start working. Don’t worry relief is on the way!

We also give you a chance to have some control over your pain relief during labor. Starting in February 2013, St. Luke’s and Anesthesia Associates will utilize a patient-controlled button for delivery of your medicine. When your contractions start to become too strong, just push the handy button and more medicine will be “pumped” into the epidural. We place the epidural, set the pump, give you the “button” for control and troubleshoot problems should they arise. All you need to do is have your child!

-

What is an epidural catheter?

An epidural catheter, called "epidural" for short, is a tiny tube that delivers pain medicine directly into the area in your back around your spinal cord. This area is called the epidural space.

An epidural can be used during childbirth to partially or fully numb the lower body. The amount of medicine you get through the epidural will affect how numb you are. A low dose of medicine will decrease pain, but it usually will allow enough feeling and muscle strength to push during contractions. A higher dose of medicine may block all feeling and may make it harder for you to push. In most cases, the epidural medicine can be decreased or stopped if it makes it hard to push. Because an epidural decreases feeling and strength in the lower body, most women cannot walk while they have an epidural.

For some women an epidural may slow down labor, while for others it has no effect on the length of labor or may make labor go faster.

It usually takes about 10 minutes for the pain medicine to begin to work. It may take 15 to 30 minutes to get the full effect.

The medicine that you get through an epidural is unlikely to affect your baby.

An epidural also can be used to block pain during a cesarean section (C-section), when the baby is delivered through a cut (incision) that the doctor makes in the lower belly. Having an epidural allows you to be awake for the delivery of your baby.

-

I’m thinking of having a labor epidural. What should I be concerned about?

There are approximately 4 million births yearly in the United States- 2.4 million involve neuraxial analgesia*. Epidural, combined spinal-epidural and spinal analgesia are generally safe and effective for pregnant women. However, as with every medical procedure, there are risks involved. This narrative is to help inform the patient about some of the potential risks of neuraxial analgesia for labor and Cesarean Section.

Please let your anesthesia provider know if you have any nerve, muscle, heart, lung, or coagulation diseases, or if you have had any back injuries or back surgeries.

If and when you are laboring – It is strongly recommended that you consume only clear liquids (pulp free juices, energy drinks, soda, black coffee, etc.). Eating can increase the risk of vomit entering your lungs should you require urgent/emergent general anesthesia for a cesarean section.

- Multiple attempts required to successfully place the epidural catheter: This is more likely with individuals with low back disease, back surgeries, and obesity. If you have spinal instrumentation please inform your anesthesia provider.

- Pruritus (itching): This occurs in approximately 40% of laboring women with epidurals and usually gets significantly better after the first hour. Pruritus is likely a side effect of the epidural or spinal medication. There are treatment options for persistent itching(1).

- Nausea and Vomiting: Nausea and vomiting occurs frequently during pregnancy and labor. There are many interwoven causes of nausea and vomiting during labor. Epidural analgesia may increase, or decrease, the frequency and severity of nausea depending on the circumstances. Emesis can occur up to 60% of patients having anesthesia for cesarean section.

- Incomplete analgesia (pain relief) or anesthesia: Approximately 5 to 30% patients get some degree of inadequate analgesia with labor epidurals(2). Epidural analgesia is often effective for the contraction pain, but will likely not eliminate “back labor” and “pushing pain.” There is typically a 5% risk of epidural catheter replacement due to inadequate analgesia(3). The failure rate of spinal anesthesia for Cesarean Section is less than 2%(14). Failure of a spinal anesthetic will likely result in general anesthesia.

- Back pain after delivery: 30 to 50% of women have low back pain after delivery. Although the epidural site may be sore for several days, studies have yet to find a relationship between epidurals and long-term back pain. Inability to return to prepregnacy weight is the largest risk factor(1).

- Low blood pressure after epidural placement: This occurs in about 10% of women with labor epidurals. This may result in lower blood flows to the fetus. You will be monitored and low blood pressure will be treated with fluids and medications if necessary(1).

- Prolonged second stage of labor (the pushing stage): Neuraxial analgesia may prolong second stage of labor by 30 to 60 minutes(4,5) and may increase your risk of an instrumented delivery from 3% to 9% (6). The prolonged labor does not seem to be harmful to the baby as long as he/she is tolerating labor(7).

- Fever: This occurs in approximately 15% of laboring women with epidurals compared to 1% of laboring women without epidurals. It does not appear to be due to infectious causes(8).

- Unintentional dural puncture and headache (the spinal headache): Dural puncture can occur in 1-3% of women with a postural headache resulting 50 to 70% of the time(9). The headache is initially treated with fluids, caffeine, analgesics, and rest. It can last 1-2 weeks if left untreated(1,6). If those interventions fail, an epidural blood patch can be performed which is 75% to 85% effective(1,6). Sometimes a second blood patch is necessary to improve the headache.

- Bleeding: The risk of bleeding developing around your spine (Epidural hematoma) is very rare if no pre-existing bleeding disorders are present. The risk is estimated to be 1 in 168,000(10).

- Infection: The risk of an infection developing around your spine (Epidural abscess) is also very rare if you presently don't have infections or an immunocompromised condition. The risk of epidural infection is between 1 in 12,000 to 500,000(10,11).

- Fetal heart rate abnormalities: Your baby’s heart rate may slow temporarily after initiation of neuraxial analgesia. This is likely due to decreased levels of maternal catecholamines (adrenaline). There does not appear to be any increased risk of poor fetal outcome(1).

- Nerve injury: In a recent study the risk of nerve injury was found to be about 1%. Risks included: first time labor and duration of pushing, but not neuraxial analgesia. The most common injuries were to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and femoral nerve. The injuries resolved, on average, in 2 months(12). It is estimated that the risk of nerve injury resulting directly from neuraxial analgesia is 1 in 240,000 for injury lasting greater than one year and 1 in 6700 for injury lasting less than one year(10).

- Adverse response to medication (allergic drug reaction, Horner’s syndrome, etc):These responses are often impossible to predict, but are fortunately very rare. There are no studies large enough to quantify these risks.

- Maternal life threatening morbidity (illness): In a prospective review of 10,995 labor epidurals, although there were no deaths, there were two serious complications requiring life support but with ultimately good outcome(13).

- Risks involved with urgent/emergent general anesthesia for Cesarean Section or emergent gynecological surgery: Pregnant women are more likely to have vomit go into their lungs with general anesthesia, have difficulty in placement of a breathing device used for general anesthesia, have increased bleeding, and have awareness under general anesthesia. Although these risks are very low, they are not zero(1).

*Neuraxial analgesia includes epidural analgesia, combined spinal-epidural (CSE) analgesia, and spinal analgesia.

If a dural puncture occurs, your anesthesiologist may choose to place an intrathecal catheter for labor analgesia (continuous spinal catheter). This often provides superior pain relief when compared to an epidural, and may also decrease the risk of developing a headache.

References:

1. Chestnut, Polley, Tsen, and Wong (2009); Chestnut's Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice, 4th Edition.

2. Hermanides, J., Hollmann, M. W., Stevens, M. F., & Lirk, P. (2012); Failed epidural: causes and management. British journal of anaesthesia, 109(2), 144–54.

3. Paech, M. J., Godkin, R., & Webster, S. (1998); Complications of obstetric epidural analgesia and anaesthesia: a prospective analysis of 10,995 cases. International journal of obstetric anesthesia, 7(1), 5–11.

4. Halpern SH, Leighton BL: Epidural analgesia and the progress of labor. Evidence-based Obstetric Anesthesia; 2005:10-22.

5. Sharma SK, McIntire DD, Wiley J, Leveno KJ (2004); Labor analgesia and cesarean delivery: An individual patient meta-analysis of nulliparous women. Anesthesiology; 100:142-148.

6. Eltzschig, H. K., Lieberman, E. S., & Camann, W. R. (2003); Regional anesthesia and analgesia for labor and delivery. The New England journal of medicine, 348(4), 319–32.

7. Roberts CL, Torvaldsen S, Cameron CA et al (2004); Delayed versus early pushing in women with epidural analgesia: a systematic. BJOG.Dec;111(12):1333-40.

8. Kapusta L, Confino E, Ismajovich B, et al. (1985); The effect of epidural analgesia on maternal thermoregulation in labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet; 23:185- 189.

9. Choi PT, Galinski SE, Takeuchi L et al. (2003); PDPH is a common complication of neuraxial blockade in parturients: a Can J Anaesth. May;50(5):460-9.

10. Ruppen, W., Derry, S., Mcquay, H., Moore, R. A., & Sc, D. (2006); Neurologic Injury in Obstetric Patients with Epidural Analgesia / Anesthesia, (2), 394–399.

11. Reynolds, F. (2008); Neurological infections after neuraxial anesthesia. Anesthesiology clinics, 26(1), 23–52, v. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2007.11.006.

12. Wong, C. (2003); Incidence of postpartum lumbosacral spine and lower extremity nerve injuries. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 101(2), 279–288.

13. Paech, M. J., Godkin, R., & Webster, S. (1998); Complications of obstetric epidural analgesia and anaesthesia: a prospective analysis of 10,995 cases. International journal of obstetric anesthesia, 7(1), 5–11.

14. Pan PH, Bogard TD, Owen MD; Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia: A retrospective analysis of 19,259 deliveries. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004; 13:227-233.

Eric Deutsch MD 01_2013

-

Epidural Educational Video

-

Epidural Education Video (Spanish)